California doctor attends Zoom court hearing during surgery: ‘I’m in an operating room right now’

Unbelievable.

www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/03/01/california-doctor-zoom-court-surgery/

(Click link to access article)

Unbelievable.

www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/03/01/california-doctor-zoom-court-surgery/

(Click link to access article)

“The Power of Informed Consent,” by Peter Mullenix and Patrick Malone, Trial magazine, December 2020.

Download the PDF Version Here – The Power of Informed Consent

People with chest pain and trouble breathing need to see a doctor within minutes to determine whether the issue is life threatening. But a 25 year old Milwaukee woman suffering from an enlarged heart waited in an emergency room for three hours with these symptoms, before finally giving up. She had been told she might have to wait six more hours, so she decided to leave and try to get help at an urgent care facility. She stopped to get her insurance card on the way, and collapsed. She was beyond saving by the time an ambulance arrived. More details here.

I got to do something cool on Friday (April 19, 2019): watch a bill I helped propose get signed into law by Governor Inslee. It all started a couple years ago when I went with some other members of our local patient safety group (Washington Advocates for Patient Safety) to a national conference on patient safety. One of the presenters at that conference was a reporter from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who had been behind an amazing investigative series about doctors, across the country, who sexually abuse patients but are nonetheless allowed to keep practicing by their State medical boards. Then, earlier this year, California passed a law requiring that doctors under sanction for sexual misconduct have to tell their patients about the sanction.

We (WAPS) looked at our laws and realized that doctors in Washington could be disciplined for sexual misconduct, return to practice, have special conditions imposed on them by the State medical board related to their misconduct, but the other patients of the doctor would never be told. They wouldn’t know their doctor had been found to have committed sexual misconduct.

That seemed like a recipe for disaster, so some members of our group started meeting with our reps and senators. We wanted our state to pass the same new protection that California passed: doctors have to tell patients when they have been sanctioned for sexual misconduct. We got the most interest from my West Seattle representative, Eileen Cody, a democrat. She then took the idea and worked with a republican, Michelle Caldier from Port Orchard. The two of them wrote up a bill, and it sailed through both the state House and state Senate unanimously, largely due to work by the founders of our group, Rex Johnson and Yanling Yu. (Also, the timing didn’t hurt, with #metoo and Larry Nassar still fresh in everyone’s minds.)

On Friday, we had the signing ceremony in Olympia. It was awesome. You go into this big fancy room, with the reps who sponsored the bill, and the governor sitting in front of the bill he’s going to sign, at the head of a big fancy table. You *very* briefly introduce yourself, he says about a 10 second speech about the bill, and then, he signs. And just like that, our idea became Washington state law. Then they take a few pictures and hand you an official governor signing pen as a souvenir.

Really felt good to see the system work like it should to protect patients from sexual abuse. If you happen to be from Rep. Cody or Rep. Caldier’s districts, don’t be shy about letting them know you’re glad they took on this work. Cody: (360)786-7978; Caldier: (360)786-7802.

And if you have an idea for a law that should be passed, you should think about calling your rep and trying to arrange a time to talk, to explain why you think a change is necessary. Believe it or not, they are very receptive to that, particularly if you’re from their district. We ended up meeting with Rep. Cody at C&P Coffee in West Seattle. Got to eat a cookie, and didn’t even have to put on a suit. (Though I did put on a suit for the Governor.)

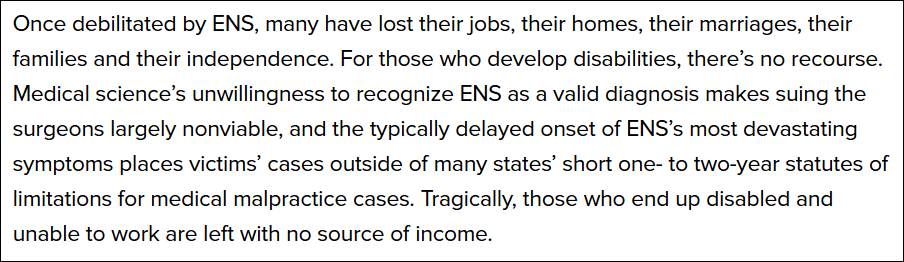

As you read this excellent writeup of what it’s like to experience “Empty Nose Syndrome,” I bet you’ll take note of your breathing. If you’re like me, you won’t be able to stop thinking about it. It was particularly persuasive to me, as I had read this while lying in a hospital bed with a “nasogastric” tube inserted, quite unpleasantly, from my nose to my stomach.

Regardless, everyone who is considering sinus surgery should read it. And according to statistics from 2006, that’s a lot of people. Roughly 600,000 per year. And it does look like the medical community is taking notice. There have been eight publications with “empty nose syndrome” in the title this year alone, according to my PubMed search.

But with that many surgeries happening, you can bet there are some doctors who still don’t know. So patients need to protect themselves and bring the issue up with the surgeon. If the surgeon doesn’t take the concern seriously, shop for another one. Otherwise, you could end up like these people:

Luckily, for patients in Washington State with ENS, the laws are slightly better. They should have a year from discovery of ENS, so long as suit is filed within eight years of the initial surgery. And Washington, unlike other states, places no tort caps on the value of lost homes, marriages, families, and independence. So if you are a Washington patient with ENS, and you weren’t warned about it before your sinus surgery, talk to a qualified medical malpractice attorney as soon as you can.

And if you’re a sinus patient, don’t worry about making your doctor uncomfortable with too many questions. You don’t get a second chance.

Patients assume that, if they are harmed by a medical error, two things will occur. First, their medical professionals will rally around them to prevent the consequences of the error, pulling out all the stops to leave the patient good-as-new. Second, if there are problems that can’t be fixed, attorneys will throw themselves at the patient to help them sue the doctor who made a mistake.

Neither is a realistic picture. Injured patients often find themselves abandoned by the doctors whose error caused the problem and unable to find a new care team. This is because the other doctors want to avoid a situation that might require them to criticize a colleague. Moreover, as explained below, finding a lawyer for a medical claim can be nearly impossible.

Why?

The short answer is that the system – which includes the medical system and the legal system – is not set up to ensure compensation for injuries caused by medical errors and defective medical products. Often, only the most horrifically, egregiously, injured patients will draw interest from attorneys for patients. And it’s only a subset of those cases that will actually end in a worthwhile settlement or verdict for an injured patient.

Walk a mile in your lawyer’s shoes.

To understand these issues, you need to put yourself for a moment in the shoes of the average patient’s lawyer. Here are some things you should know about yourself.

Running your office is expensive. You need to have an office for client meetings and depositions. You want the office to inspire confidence, so it’s gotta be nice. You need staff for that office, and that staff needs health insurance. You need expensive equipment and supplies. You have to pay for legal books and research services. You need malpractice insurance.

You work on contingency. You don’t have a steady stream of income. This is because your clients can’t afford to pay the hourly rate for your services that would keep your doors open. In contrast, the lawyers for doctors and manufacturers are almost always paid an hourly rate by an insurance company. But you get paid only when your clients do, so you have an agreement with them to take a percentage of any recovery you help them get. Each case is expensive. Unlike car crash cases, divorces, and small criminal matters, cases against doctors and medical product manufacturers require lots of professional experts. These experts do not work on contingency, meaning the attorney (you) must pay their expenses as the case progresses, well before any attorney fee is earned.

It’s hard to overstate how significant this issue is. Costs in a complex medical case can run in the hundreds of thousands. How? Take, for example, a case against a medical device company that made a product that malfunctioned during a surgery, causing lifelong internal problems. To win such a case, you’ll need to figure out why the product malfunctioned. Was it a design problem or a manufacturing problem? Both? Should the warnings have been different? You’ll have to pay at least two different engineers to look at that issue, which will require them to review tens of thousands of pages of documents. You pay for each hour in which they do so. Once you have that figured out, you’ll need to figure out if the product was misused by the doctor. You’ll have to pay a surgeon to figure that out. Then you’ll need to figure out if the subsequent treatment, after the surgery, was appropriate. That means you’ll need to pay those subsequent doctors to talk them; this could be as many as 20 different specialists, depending on the injury. Then, for at least some of those specialties, you’ll need to pay to have an independent review of their work. This is because the device company will blame the care team, or the patient, for the problems that occurred.

We’re not through with the experts yet. You’ll need an expert to put together the all of the medical expenses that are attributable to the original injury from the surgery. That expert (or perhaps another) will need to prove that those costs were reasonable, so that you can recover them for the client. You have to pay a psychiatrist or psychologist or neuropsychologist to evaluate your client’s mental health damages. Your client can’t work anymore, so you need to hire a vocational rehab specialist to show why lost wages are appropriate. You need to order tens of thousands of pages of medical records to make sure your experts are properly informed. And you need to hire an economist to figure out much money needs to be paid now to make sure the eventual settlement or verdict properly accounts for interest and inflation.

Then, when you actually file the case in court, you have to keep these experts up to speed as new information comes in. The manufacturer will take depositions of each expert. This means you need to work with the expert before each deposition (cringing at the hourly rate), to make sure they don’t say something that can be taken out of context at the trial. The manufacturer will also hire its own experts. You need to depose those people, probably each one. To depose them, you have to pay their hourly rate. And often, the manufacturer will disclose multiple experts on a given topic, forcing you to depose more than one expert. Some of these experts charge more than $1,000 per hour.

These depositions carry their own costs. You have to pay both hourly and flat fees for for a neutral videographer and a neutral court reporter. For many of the experts, you’ll need to travel across the country for the deposition. You’ll have to pay for the airplane, the hotel, the rental car, the expensive food. Even for local depositions, you’ll have to pay for smaller things like parking. You have to pay for the transcripts and videos themselves. The little things add up.

Then, as the case progresses, the manufacturer will try several times to attack your experts’ testimony in an effort to have the case limited or thrown out. These attacks will each require you to spend time with your experts to rebut or stave off the attacks. So the bill keeps growing.

You will be required by court order to have a “mediation” of the claim. This most likely means you and the manufacturer will split cost, in the thousands, of a former judge or high profile attorney in an attempt to negotiate the claim.

And then comes the trial. You need video equipment for the courtroom. You and your staff need hotel rooms and transportation to court. You need food for your entire team. You need to make sure each of the witnesses will be in court on time. You have to pay fees to have subpoenas served. You have to pay for your experts to fly across the country for the trial, and you need to put them up in a hotel nice enough to keep them happy.

Opportunity Costs. When deciding whether to take a case, you also have to take into account the opportunity costs. If you commit to take this case, how much of your time will it consume? Will it mean you can’t take on a better case that you don’t know about right now? The aphorism passed down by plaintiffs’ lawyers is that a firm makes 90% of its income from 10% of its cases (but does 90% of its work on cases bringing in the 10%). The trick is trying to figure out whether the case you’re thinking about taking on will be the one that puts you over the hump for the year, or whether it will suck your time and money away only to be resolved for a relatively small amount. This is what’s lingering in the back of your mind as you decide whether to take on each new potential injured patient.

Time to Payoff. Not only are your investments uncomfortably large, but it can take a really long time for them to pay off when they are successful. Even after filing, cases generally take 2-4 years to bring to trial. And if trial is successful, the defense appeals. That can add another 3-4 years. And here’s the kicker: in federal court, the interest on a successful jury verdict as of the date of this writing would earn interest at only 1.8%. That means defendants have every incentive to drag the appeals process out as long as possible by requesting postponements and bringing appeals with shoddy merits.

The cases are hard to win. Jurors want to feel like they live in a safe world, like the thing that happened to your client could never happen to them. Jurors see doctors as helpers, doing their best in a difficult situation. Jurors don’t want to stand in the way of medical progress, and worry what affect a verdict against a medical product manufacturer might have. Jurors have been trained, through decades of propaganda, that people who bring lawsuits are just seeking a handout. They are told that plaintiffs, even patients injured by clear medical error, are not to be trusted.

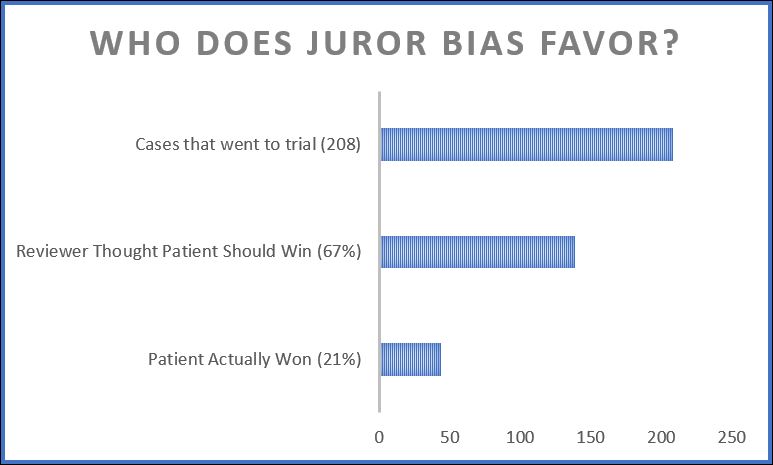

All of these innate juror feelings add to the degree of difficulty of a medical lawsuit. A great study in 2009 on juror treatment of malpractice claims crystallizes the problem. It found that doctors win about three of every four cases that go to trial. They even win the cases they should lose. To show this, the researchers had independent doctors review 208 closed insurance files for cases that were eventually tried. Based on physician reviews of those files, patients should have won 67% of the cases. But the patients actually won only 21%. When you’re winning less than a third of the cases you should win, there’s a bias you need to recognize.

Laws that take away remedies. As hard as it is to convince a jury that you should win, you can still lose even after a jury says you win. For example, imagine you have a former triathlete as a client, but that client ends up having both legs amputated because of a clear medical error. A jury decides the lost legs should be valued at $10 million. (Your client was, after all, using them every day.) If you are in California, that $10 million is reduced to $250,000, likely not even enough to pay all of your experts. Many other states have similar (awful) laws.

Medical product manufacturers also have it good. If their product receives a certain kind of approval from FDA, that fact simply cuts off most kinds of lawsuits against them. They have special laws protecting them in discovery. (Doctors do too.) And some states even cap damages in product liability lawsuits. Likewise, in some states, there are no punitive damages available, even when it is shown that the manufacturer has recklessly ignored a danger to patient safety. If you’re going to bring a medical lawsuit, you need to recognize that you’re swimming upstream.

The takeaway. What all this is meant to show is that winning cases on behalf of injured patients is difficult, expensive, risky, and slow. Because of that, lawyers for patients have to be extraordinarily careful about which cases they commit to go forward on. This means injured patients will often – in their time of greatest need – hear a “no” from several attorneys.

How can injured patients increase their chance of finding a lawyer?

Patients come to lawyers when at their worst. They have been dealing with chronic injuries, stonewalling from doctors, lost work, and insurance problems. They can’t do the things they used to enjoy. This all puts stress on marriages and families as well. Under these difficult circumstances, it is easy for patients to be, well, impatient.

Being rejected by attorney after attorney under these circumstances only adds to this, worsening the already significant trauma from the medical error. The patient feels abandoned and hopeless when no attorney will take the case. So what can a patient do to help avoid rejection?

Know what the attorney is looking for.

The attorney is looking at four primary things when evaluating a potential new case: an obvious mistake or malfunction; a serious, permanent injury; clear causation; and collectability.

An obvious mistake will take fewer experts to prove and lower the chances of losing. How do you know if you have an obvious mistake? There are lots of good indicators. Did the surgeon apologize or admit error? (This matters even in states where the apology might not be admissible, as it gives a clue to the lawyer that this is a real error and not just a bad outcome.) Do the medical records document the mistake? Do they say a product malfunctioned? Have other doctors told you it was a mistake or a bad product? If it’s a product, has it since been recalled? You want to find all of the information you can to show the lawyer: Don’t worry, we’re gonna win.

When looking at the injury, lawyers are looking for a few different things. Is the injury something that causes chronic, permanent problems, or was it a discrete event of unnecessary (but transient) pain? Does the injury affect something you have shown you love to do? Does it impact your ability to raise your children? The lawyer will also be curious about the medical bills. Will this require a lifetime of treatment with different specialists? Have there already been multiple surgeries to fix the problem? Are your other doctors willing to speak to the attorney?

As to causation, the attorney will want to know how you can show that the mistake/malfunction caused the injury, as opposed to some other cause. How do we know that missing the cancer diagnosis actually led to death? How do we know the bowel perforation was caused by the malfunctioning instrument, and not some natural cause? How do we know the loss of the ability to do the things you love actually happened because of the surgery, and not some other, unrelated medical problem? Defense attorneys are ruthless in blaming things other than the doctor and/or product. The attorney you speak to needs to have a reason to think they can rebut those arguments.

The collectability issue in medical cases is often less significant: doctors, hospitals, and product companies are often quite wealthy. But collectability can still be an issue. Was the doctor’s conduct intentional, such that insurance might not cover it? Was the doctor on staff at the hospital, or will you be limited to only the doctor’s insurance policy. Is the company that made the product now defunct? Bankrupt? Has it exhausted its insurance on other payouts to other injured people. Most attorneys will not expect you to know these things, but they will be on the attorney’s mind.

Collect your records. Patients can now get their own medical records fairly cheaply under the recent “HITECH” Act. You can jumpstart the process of investigating your case by going to the hospital/clinic and telling them you’d like to do a “HITECH request” for all of your records. You can’t have too many records. Some providers will resist this and try to charge too much. But the cost should be very cheap: if the provider seeks to charge you more than $25, it’s probably too much. You don’t need to fight with the provider on this: if they want to charge too much, you can wait and have the attorney get the records. But if the clinic/hospital is being reasonable, you will be able to have all of your records before speaking to the attorney. That’s a bonus. Bring them on a thumb drive or figure out how to send them electronically. Then, select out the most important documents: the operative note, the discharge note, and any emergency room admit records. If you believe the mistake was made during a surgery, get the anesthesia records as well. If one of your records shows causation, pull it out and highlight it.

Document your follow-up. Keep a calendar with all of the doctors, physical therapy, and counseling appointments. Anything related to the injury. Document every visit. Document how long it took. Keep track of the work you missed. Keep track of the medications you take, and what you spend on those. If a doctor says something that you think is important, write it down in your calendar. Medical records often have key omissions, so documenting things yourself can strengthen your claim.

Stay off of social media. Defense attorneys are looking for things to make you look bad, and Facebook/Instagram/Twitter are usually the easiest places find those things. They will look for pictures that they will pull out of context to argue you are not really hurt. They will look for statements of blame. They will look for sources of stress (work conflicts, family arguments) that have nothing to do with the case. And they will look for ways to learn about your personality, so they can manipulate you during your testimony. You don’t need to give them that ammo. Just stay off of social media during your lawsuit.

Collect photos. Put together photos that show what you were like before the incident. Things that illustrate what you will eventually want to tell the jury. Bring those photos with you to any meeting with a potential attorney. Electronic copies are better.

Be patient, but not too patient. The attorneys you speak to have a lot going on. They have cases they are already responsible for. They have other cases they are “screening.” They have families and office politics to deal with like everyone else. So don’t be alarmed if a week goes by without communication. With that said, however, do follow up. Cases have statutes of limitations, and you need to protect yourself. So at the initial meeting, be sure to ask the attorney’s opinion on the statute of limitations. Then, be assertive enough to check in every two weeks, to see if there is more information you can provide the attorney. When you do so, be careful of your tone. You don’t want to seem like a complainer. No one wants to sign up a difficult client. So simply use a professional tone, ask for a status update, and limit your check-ins to every two weeks.

Don’t talk to just one attorney. There is no law against talking to more than one attorney at a time. Each attorney will have a different risk tolerance. Talking to multiple attorneys thus gives you multiple chances to find the right fit.

With that said, don’t hide the ball. Be honest with each attorney about the fact that you’re still shopping for a lawyer. Ironically, this will often actually make your case more attractive, and increase the urgency the attorney feels about your case.

Don’t give up because one says no. Rejection can be crushing, but it only takes one “yes” to move a case forward. I have gotten seven-figure settlements for clients who had been rejected by multiple other attorneys. Every attorney will see angles in a case that other attorneys might miss. So be as persistent as you are patient.

How do I pick between lawyers?

Some injured patients are lucky enough that finding one attorney isn’t the problem; choosing an attorney is. So how do you choose between several accomplished attorneys? Below are the traits I would use if choosing a lawyer to represent someone I love.

Candor. I think this is the most important. When you talk to the lawyers, are they trying to give you a realistic idea of what years of litigation will be like, and whether it’s worth it? Are they telling you the good parts as well as the bad? Or are they making it seem like once you sign up the other side will simply throw a truckload of cash at you?

Case-Specific experience. If you’ve got a malpractice case, does this lawyer specialize in that kind of case? If it’s a device case, have they done such a case before? Or have they made their bones on other kinds of cases, and you’ll be their guinea pig in this case? Most people know at least one lawyer. Talk to that person: what does he or she say about how useful this lawyer’s experience is? You would not go to a cardiologist for a knee problem: so find a lawyer who focuses on your kind of case.

Do they go to trial? Defense attorneys love litigation, but many hate trials. A bad enough loss at trial can lose the client/insurance company for the defense attorney. For this reason, insurance companies and manufacturers will place a higher settlement value on cases where the patient’s attorney has a demonstrated track record of actually taking cases through to trial. So that’s the kind of lawyer you want to find. And don’t just believe the lawyer when he says he goes to trial. Ask for specifics. If you know a lawyer, ask that lawyer what this lawyer’s reputation is. What will the defense attorneys learn when they research your lawyer?

Resources. I wish this weren’t an issue, but resources matter. You want your attorney to feel comfortable spending what needs to be spent to work your case up. So ask the attorney what they would budget for costs for your case. What would they be willing to spend? Are they able to see the case all the way through trial, if necessary?

What doesn’t matter? When I’m evaluating a patient’s attorney, I care little about what law school s/he went to. There are outstanding attorneys from lower tier law schools. There are attorneys from Harvard and Yale whom I would never hire. Similarly, many lawyers will brag about various honors and awards on their websites. The vast majority of these honors are not worth the pixels devoted to them. In fact, some honors can be bought by the lawyer who gets them for a fee. Focus more on experience in similar cases, willingness to go to trial, prior verdicts, and candor. Do not fall for an attorney who is simply telling you what you want to hear.

What will litigation be like?

You’ve found your attorney, and you’re moving forward. What should you expect? There are three different things I try to emphasize when talking to clients about the litigation process.

1. Hurry up and wait. There will be long periods of inactivity. Those will be followed by short bursts where you have to produce a lot of information quickly. And then you’ll wait again. This will go in cycles. The first cycle will involve what’s called “written discovery.” This is where the defendants serve written questions that you must answer within 30 days. The questions also include document requests. Much of what is asked for will seem unreasonable and unrelated. That’s for your lawyer to worry about: your job is to get the answers and documents to the lawyer as soon as possible. Then, as the case goes on, you’ll be asked to supplement your answers several times. That’s part of the deal. The second cycle will involve your deposition. Your lawyer may want to spend several hours preparing you for the questioning. This will involve more questions, more documents, more pictures, etc. The final cycle is the trial itself. Not only will you need to prepare for your trial testimony, but you will be crucial in helping choose which witnesses testify and arranging for that testimony.

2. You have little privacy. Your claim will involve, in some way, an argument that your life is much worse than it used to be because of the medical error or malfunction. Unfortunately, that opens up areas of your life that you would rather keep private to “discovery” by the defense. The defense will ask about your sexual relationships in almost every case. They will ask about family fights. They will ask to see the notes your counselor takes. They will ask to see your emails between friends and family. They will ask to access your private social media accounts. The more sensitive the info, the more they’ll try to get at it. And, despite your attorney’s best efforts, they will probably get some information you wish you could keep private. This is a reality that needs to be accepted early on in the litigation.

3. Discovery goes both ways. The flip side is that we also get to do discovery. We get to find out about stressors in the doctor’s life. We get to see internal emails at the hospital about your case. We get to find out things from the doctor’s past that s/he wishes were private. We often get to see how much money everyone is making, so we can know about the financial incentives that led to your injury. And when suing a company, we get to go through their internal files to find out what they really knew, and what they really care about. This is miserable for them, which is simply another unfortunate reality of the system. They fear that embarrassing information will get to their competitors. They fear media interest. And above all, they fear anything that will move your case toward a public trial that will invite more litigation from others in the future. A good lawyer will keep you updated on these positive discoveries as the case goes forward. But even if they don’t, ask them what they’ve found. You could use a little good news during this drawn-out process. And it’s important to remember that your privacy isn’t the only privacy that’s being invaded by the process.

Is it worth it?

Every injured patient should ask, before going forward, whether it’s really worth it to sue. In answering that question, the patient should be ruthlessly practical. Ask yourself: what amount of money would make a truly significant difference in my everyday life? What is too small to justify a suit? Then ask your attorney(s) what chance s/he thinks there is of getting that much money after all is said and done. If the chance is low, you may not want to bring the case. The down sides, in terms of intrusion in your life and invaded privacy, may simply not be worth it.

With that said, most patients undervalue their cases. Many patients say they just want medical bills and lost wages paid back, when in reality those are often the least important parts of their case. Moreover, case value often depends on how bad the conduct of the defendant was. The worse the conduct, the less trouble a jury has with making the defendant pay for the full consequences of the behavior.

And for every client I’ve worked with, there were reasons beyond money to bring the case. When something goes horribly wrong, injured patients want to make sure it doesn’t happen to someone else. They want to know that changes are happening. Instead, they are confronted with a medical system more interested in defeating liability than preventing the next tragedy. In that situation, bringing litigation is often the only way to force a defendant to confront its dangerous behavior, to correct systems problems. That can feel good.

In other words, the decision whether to bring suit is an ultimately an intensely personal one. Only the client can make it. But becoming informed about what to truly expect by finding a lawyer whose candor creates trust is a great start.

And for those few patients who are able to bring a case, and who do win a life-changing amount to compensate their injury, there is nothing like it. Those patients, some of whom I’ve been lucky enough to work with, go from feeling like the world stepped on them to feeling like they have some power to make things better. They get help fix a flawed and dangerous system by making real change. They get to know that their bravery, their willingness to sacrifice their privacy and time, will prevent future tragedies. In short, they get to win for a change.

I met Rachel Brummert at the initial PSAN meetings at Consumer Reports last year. She is writing a book (I’ve contributed a chapter) designed to help patients who have been injured my medical errors and defective medical devices. But she needs more stories, or it won’t be published. If you have a story to share, I encourage you to contact Rachel and see if you can help her finish this book. Her email on the topic is below:

My name is Rachel Brummert. I am a patient safety advocate who was inappropriately prescribed a medication that left me disabled. After I was harmed, I made it my mission to advocate for others.

My story can be found here for some background on my journey. http://rachelbrummert.com/my-story/

As a harmed patient, I found little help or resources and I had to learn about flaws in the system by being thrown into the deep-end. It was scary and complicated, and I learned way more than I wanted to about how medications and devices are approved.

Two years ago, I was asked by Josh Rivedal to share my story in his book The i’Mpossible Project: Reengaging with Life, Creating a New You. The format of the book is storytelling.

This upcoming book is the third in the i’Mpossible Project series. I wanted stories to be told by harmed patients themselves; they could tell their story better than I could. I wanted to combine patient safety information with the storytelling format.

Also included in the book will be resources. I think it is important that patients have all the information they need to make an informed decision about their health. Harmed patients had to learn this the hard way and I feel a moral responsibility to not allow that to happen to others.

I want this book to be more than storytelling; I want it to affect change. Change in policy/legislation and change in attitude toward patients.

As I went through all of this, I felt like I wasn’t being heard; that the medical community was dismissing me. I believe patients need to be heard because we are the end result of what went wrong.

This is why I need your help. Collectively, our voices become louder and it’s hard to ignore strength in numbers.

Here is information and guidelines for chapter submission: http://rachelbrummert.com/upcoming-book-patient-safety/

You have my word that I will treat your story with the utmost of care. Your story is important to me. You retain all rights to your story. Before publication you will have to sign a waiver saying just that- you are merely giving me permission to use your story. You will also have final say after edits. Nothing gets published without your approval.

I would like to tell each and every one of you that I am so very sorry for what happened to you or your family member. Please help me shine a spotlight on much needed changes so this doesn’t happen to anyone else.

If I get enough stories by mid to late June, the book will likely be published by December 2018.

Rachel Brummert

“Any good apology has 3 parts: 1) I’m sorry 2) It’s my fault 3) What can I do to make it right? Most people forget the third part.” – Unknown

It happens over and over. Client calls because a medical error harmed them. And they think they have a rock solid case because the doctor apologized for messing up. They think that means the doctor won’t contest liability. It will be an easy win with a quick settlement.

What those clients don’t know is that “Sorry” doesn’t really mean “Sorry” — or at least doesn’t include the third component — when it is uttered by a physician in Washington within 30 days of the medical error. That’s because of a law that makes a doctor’s apology inadmissible in civil trial when the apology was uttered by a doctor. That means the doctor can apologize to you, profusely, and then, when trial comes, act like he or she did nothing wrong. And you can’t call out the hypocrisy.

The statute applies to any “statement, affirmation, gesture, or conduct expressing apology, fault, sympathy, commiseration, condolence, compassion, or a general sense of benevolence” made by the doctor within 30 days of the error. And it also applies to any “statement or affirmation regarding remedial actions that may be taken to address the act or omission that is the basis for the allegation of negligence.” Again, inadmissible. They say they’re going to change the way they’re going to do things. They say they messed up. And it means nothing.

How sincere can these statements and apologies really be if the doctors know that no consequences can come from them? That’s why, in my darker moments, I usually conclude that all of these programs are just financial risk management devices, encouraged, if not fully designed and implemented by, the doctors’ liability insurers. A *real* apology would be one where the doctor also, in writing, admits liability and waives the statute that allows the waiver to be kept secret.

So, if your doctor apologizes to you, ask him or her how sincere she is about the apology, and then ask for an admission of liability, and a waiver of all rights under RCW 5.64.010.

The FDA has proposed a change that will seriously limit the usefulness of the online database that is supposed to collect and categorize medical device malfunctions by product. In many situations, this is the only source of information patients can use to investigate the dangers of medical devices that their doctors propose to use. (Many doctors are not even aware of this database.)

Comment period ends 2/26, and you can comment here: https://www.regulations.gov/comment?D=FDA-2017-N-6730-0001

If you’re a twitter user, I wrote up the changes, and included my written comment to FDA here: https://twitter.com/SafePatientAdvo/status/966398443823407105

I don’t know how useful these comments are, but they certainly can’t hurt. Please tell them not to make this harmful change.

Back in October, I went to Yonkers, NY, the headquarters of Consumer Reports, to join a group of patient safety advocates nationwide in founding a new, nationwide network dedicated to advancing patient safety. On January 31, that idea became reality: the Patient Safety Action Network. This new group is powered by the Consumer Reports “advocacy division,” Consumers Union. We’re currently working on putting together resources for people to use to avoid becoming one of the absurdly high numbers of patients unnecessarily harmed by systems failures in health care. And we also have resources for people who have already been harmed. Go check it out!

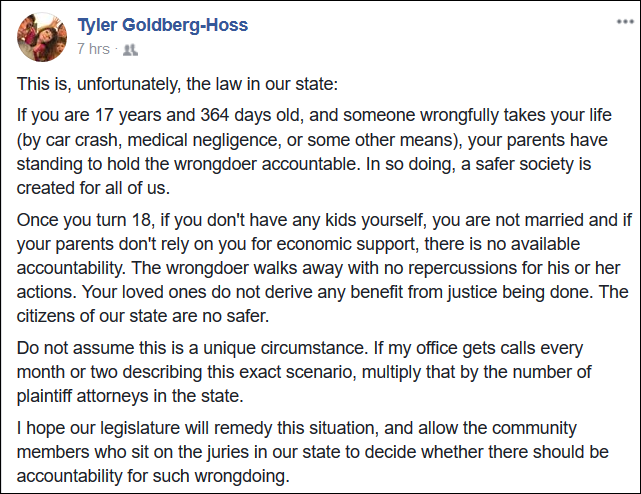

Some of our firm’s clients were featured on this story about an issue currently being debated by the Washington legislature. It’s a really important issue. A friend of mine (and an excellent medmal lawyer) shared the video on Facebook and described the issue this way:

I completely agree with him. I’ve had to explain this to potential clients several times. Nobody cares about it until it’s their family. But the law is unfair and needs to change. It’s also perverse. Under the current law, it is almost always cheaper to kill an adult who is unmarried and has no kids than it is to simply injure them. The same is true of someone with parents who live in another country. Why do we want to make it cheaper to kill these people?

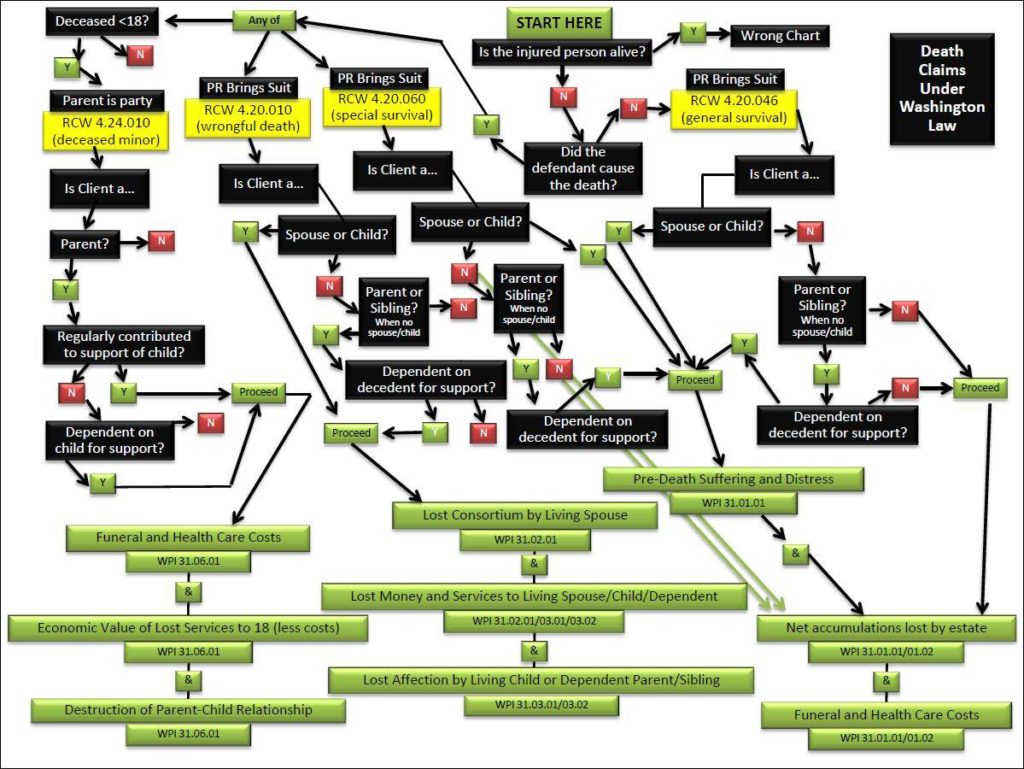

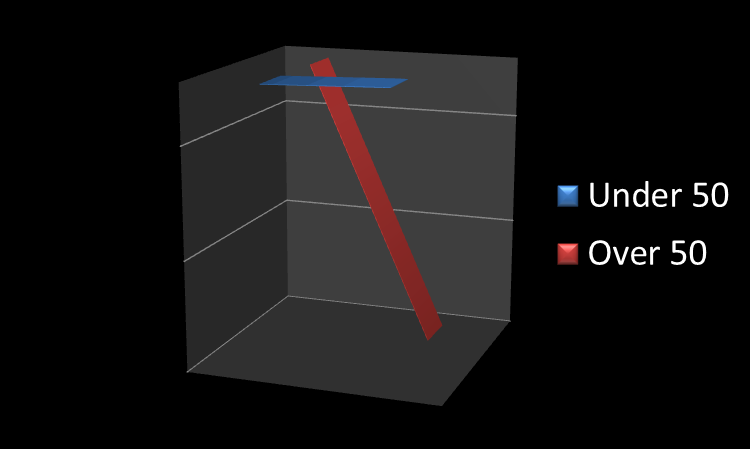

The law is also wildly, and unnecessarily, complex. For example, this is a diagram I made of the current law.

All of this is to say — I think it’s great the Washington legislature is finally working to improve this law.

For those of you who care about patient safety and live in Washington, I would really appreciate it if you’d place a short call to your state legislator saying just: “I support the proposed changes to the wrongful death law.” The laws in question are SB 5747 and HB 2262. You can get the phone number/email for your reps and senator here: http://app.leg.wa.gov/DistrictFinder/

I’ve spoken to legislators, and I can assure you these phone calls make a difference when they come from the legislator’s district. So please, make the effort. It may make the difference someday between someone you care about getting justice or getting shut out of the courthouse.

I took to twitter today to get the word out on a recent Mayo Clinic study that looks at the correlation between hysterectomy (keeping ovaries) and various health problems. The thread goes through the highlights of the study and then offers some of my own thoughts on underappreciated dangers specific to the surgeries. Please share!

A little thread on hysterectomy from someone (me) born without a uterus. Sparked by this story about a recent Mayo Clinic study… pic.twitter.com/8FU1mteMeM

— Peter Mullenix (@SafePatientAdvo) January 4, 2018

Two reporters in Los Angeles — Lisa Bartley (@tweetiela) and Jovana Lara (@abc7jovana) — have put together the best summary of the DuPuy hip implant case I have ever seen. It will make your skin crawl. They have all the internal memos, the videos of the sales team, the payouts to the doctors, and video and photo evidence of the carnage wrought. Just a truly excellent job. The video is here: http://abc7.com/health/lawsuits-over-profit-pain-and-the-hip-implant-some-call-toxic/2724100/

I hope these reporters are recognized for this work. And I hope people share this story. People simply do not realize how much money is at stake for the people in charge of our health care options: doctors and manufacturers. But once you realize the money involved, the otherwise reckless decisions start to make a lot more sense. We all need to work to make reckless decisions unprofitable.

A patient advocate friend, who I met at the PSAN Summit, has made an excellent list of questions to ask about new medications. I’d print it out before visiting any specialist, as that’s the place where you’re most likely to be asked about new drugs. And it’s a great companion to my recent list of questions for doctors about medical devices:

12 Questions to Ask If Your Doctor Brings Up a New Medication

My advice is to print them both or bookmark them so you can have them handy at the doctor.

Not every patient wants to be fully informed about his or her medical options. For the rest of us, the problem is sifting through the vast amounts of information available to focus on what’s truly significant. Worse, state laws often don’t require doctors to tell patients things that every patient would want to know. For this reason, patient safety advocates around the country are working to improve state laws to require better disclosures for patients. But in the meantime, one of the projects I’m working on (with the Patient Safety Action Network) is to come up with a list of questions patients can ask to help protect themselves, even when the law won’t protect them. You don’t need great laws if you ask the right questions.

Not every patient wants to be fully informed about his or her medical options. For the rest of us, the problem is sifting through the vast amounts of information available to focus on what’s truly significant. Worse, state laws often don’t require doctors to tell patients things that every patient would want to know. For this reason, patient safety advocates around the country are working to improve state laws to require better disclosures for patients. But in the meantime, one of the projects I’m working on (with the Patient Safety Action Network) is to come up with a list of questions patients can ask to help protect themselves, even when the law won’t protect them. You don’t need great laws if you ask the right questions.

The list below is my own, not PSAN’s, and it’s developed from things I’ve learned in my legal practice representing patients injured by medical devices. In thinking about each of those cases, there are common issues that pop up: information that could have been delivered to my clients to give them a chance to avoid the devastating outcome that ultimately led them to my law office. So I’ve tried to put together a set of questions to ask any time a doctor proposes using a medical device on you or someone you love. These are the questions designed to force doctors to show you the red flags that could have saved my clients:

There is no doubt in my mind there are other questions to ask. Probably better ones. But this is a good start, until the laws catch up. If you have ideas or concerns with this list, please feel free to contact me at: pmullenix@friedmanrubin.com

I stumbled today onto a great article from 2009 that tried to look empirically at the issue of whether jurors should be trusted to decide medical malpractice cases. The point of the article, published in Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, was to look at whether things like tort caps are really appropriate in medical malpractice. The conclusion? The idea of runaway jurors punishing doctors because they don’t understand medical issues is a myth. Instead, jurors typically awarded the same as judges. As the article puts it in the abstract:

Juries in medical malpractice trials are viewed as incompetent, antidoctor, irresponsible in awarding damages to patients, and casting a threatening shadow over the settlement process. Several decades of systematic empirical research yields little support for these claims. This article summarizes those findings. Doctors win about three cases of four that go to trial. Juries are skeptical about inflated claims. Jury verdicts on negligence are roughly similar to assessments made by medical experts and judges. Damage awards tend to correlate positively with the severity of injury. There are defensible reasons for large damage awards.

One of the most interesting parts to me concerned the issue of how juries decide cases that even doctors believe involve negligent care. One study discussed had independent doctors review closed insurance files. Based on physician reviews of those files, patients should have won 67% of the cases. But they actually won only 21% of the cases that went to trial.

In other words, the idea that jurors are unfair to doctors in medical malpractice cases is wildly incorrect. Unfortunately, that’s also the idea that forms the central premise of our Congress’s current attempt to take away the right to a jury trial in medical malpractice cases.

I think it’s the only way to make these companies pay attention: confront them with the *true* scope of the harm they caused. The City of Everett, in my home-state of Washington, announced its intention to do so in January of this year. Now Tacoma is also bringing suit. We should all be proud of the lawyers (David Ko for Tacoma, and the Kelley Goldfarb firm for Everett) and City decision-makers involved for having the courage to take these cases on.

My hope is that this is the wave of the future. Imagine how seriously drug companies will have to take these threats if these suits multiply. It’s always easy to blame the addict, but these Cities are trying to focus on the real problem: the drug dealer.

Hat tip to @ashleykgross of @KNKXfm for telling me (and her other twitter followers) about this great development.

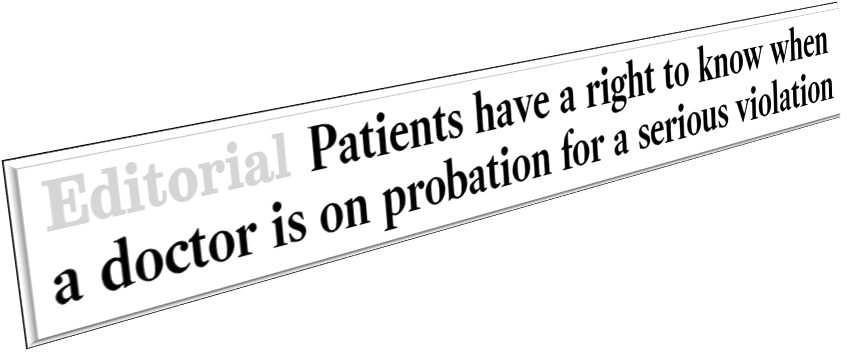

An editorial in the LA Times last Thursday needs you to read it. It explains the demise of a recent bill that would have required “physicians disciplined for serious violations to notify patients that they are on probation, and why.” The bill failed because it was “strongly opposed by the California Medical Assn.”

It’s difficult to imagine *any* legitimate reason for resisting such a disclosure rule. And it’s difficult to imagine any other profession successfully blocking such a disclosure rule. But we are all less safe when our doctors do not have to tell us they are on probation.

Hat tip to Rex Johnson of Washington Advocates for Patient Safety for passing this along.

Since I started representing people injured by medical devices, one of the most useful tools I’ve found is the Open Payments website. Open Payments is a feature of Obamacare added by a Republican, Chuck Grassley. It requires drug and device companies to report their financial transactions and gifts to doctors and hospitals.

It’s pretty surprising stuff. Surgeons — who consider themselves completely independent — routinely have received multiple $200+ meals from companies that make the devices they use. Why would the companies spend that money unless they thought it was getting something? Knowing the amounts paid at least gives the patient a chance to research cheaper or more effective alternative treatments.

A new article from The Chronicle of Higher Education looks at a different type of disclosure rule: the rules set by universities regarding disclosures by researchers of industry payments. The point of the article is that disclosure is not enoughbecause the doctors with the conflicts are *still* given the opportunity to publish their opinions. Those opinions, unquestionably biased, thus still influence other doctors’ treatment decisions. The article shows the example of a set of treatment guidelines related to treating depression with drugs published in the journal CNS Spectrums. The article is written almost exclusively by authors with money ties to the companies that make the drugs that are recommended in the guidelines. Many of the drugs recommended have never been shown to perform better or safer than cheaper alternatives.

The article then focuses different ways doctors have been able to game the system to avoid the universities’ financial disclosure requirements. It is extremely well written and highly recommended. As always, the reminder to patients is to always ask questions of the doctor when treatment is recommended. Are there any other treatments I could consider? Have you ever received money from any of these companies? Is this an on-label or off-label use? What are the side effects? What could go wrong? Have you ever done this before?

A friend of mine on twitter asked me today what I think of the House republicans’ latest version of “fixing” medical malpractice litigation. I’ve been wanting to talk about these things for a while: the proposed fixes will do far more harm to patients than good for doctors. It will remove incentives to keep things safe, and it will needlessly eliminate valid, meritorious medical malpractice cases, without getting rid of the (already extremely few) frivolous ones. Here is my (lengthy) response.

Some kids have very little luck, and I recently met the moms of three such kids. All three kids have “trach” (tracheostomy) tubes, and all three kids were sensitive to cow’s milk. For that reason, shortly after birth, all three kids went on Nutricia’s “Neocate” formula as their primary source of nutrition.

The results were disastrous. Broken bone after broken bone. Eventually, each kid was diagnosed with hypophosphatemia: an absence of the phosphate needed for strong bones. Another name for this problem is Rickets. Either way, it means extremely weak bones. And it meant years of misery for each of these families. One child, aged three, suffered 30 broken bones. The damage is permanent.

The Neocate, from all that’s known, was the problem. The company that makes it, Nutricia, knew about the problem by October 2015 at the latest. But families depending on Neocate to feed their sensitive kids did not find out about the problem until much later. Nutricia now admits the problem.

In 2017, the journal Bone published an article signed off by 21 authors from places like Yale and the Mayo Clinic and Walter Reed. Their conclusion is simple: 51 kids had otherwise unexplained “hypophosphatemia.” Most had complex illnesses and had been fed *solely* with Neocate. 94% of these kids had rickets. That means, as shown below, their bones were too weak to avoid breaking. Taking kids *off* Neocate strengthened their bones, though often permanent damage had already been done. The picture below is a before-and-after: on the left is a kid being fed by Neocate, and on the right is the same kid after he was taken off the Neocate. The results are striking: the bones on the right look so much stronger. The 21 authors all decided to “strongly recommend” careful monitoring for kids on Neocate.

There’s an easy fix: if your kid uses Neocate as his or her primary source of nutrition, make your doctor reads the study linked above. There is no reason for your family to go through what the families that called me went through.

Last night I got to see a presentation at the Mercer Island Public Library in Washington state. The presentation was jointly put on by an energetic group of patient safety advocates from Consumer Union, which is the “policy and mobilization arm” of Consumer Reports, and the Washington Advocates for Patient Safety. The attendees were just regular people who responded to an email invitation from Consumer Reports because they wanted to know more about protecting themselves from preventable mistakes in the hospital context.

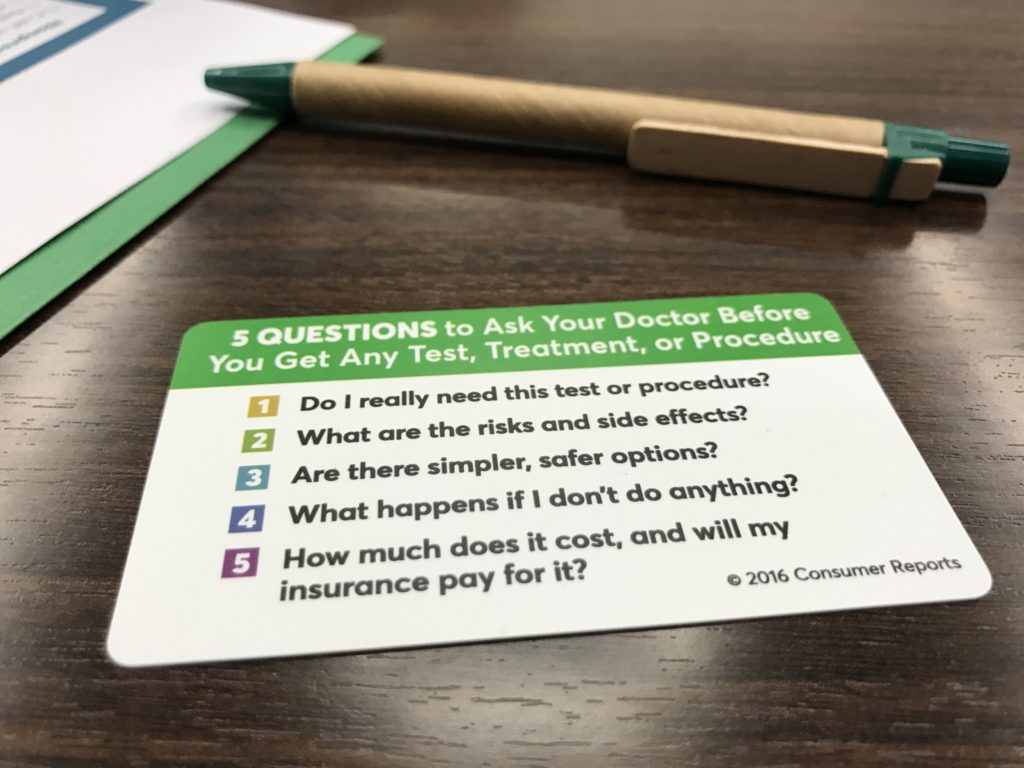

The best takeaway was the list of five questions we should all ask our doctors every time they propose to do something. Those questions are above. But there was a lot more. For example, we got a tutorial in the Consumer Reports Hospital Ratings, and learned six things we should know about every drug we take. (I’ll put those up in a later post.) The presentation was fantastic, and I recommend anyone who gets the chance to go to one do so.

Medtronic Mechanical Circulatory Support is recalling its HeartWare Ventricular Assist Device (HVAD), a device that helps the heart deliver blood to the rest of the body. Patients with end-state left ventricular heart failure or those waiting for a heart transplant are affected by the recall. The company discovered a loose power connector could cause the rear portion of the pump’s driveline to separate from the front portion. This could allow moisture to cause corrosion and electrical issues, affecting the speaker volume on the device. If the speaker volume is not working, the patient might not be able to hear warning signals coming from the device.

Medtronic is also recalling its “Splice Kit” for the HVAD. Medtronic says it discovered that a design flaw with the repair cable in the Splice Kit made the HVAD vulnerable to shutting down from wear-and-tear forces. If the device shuts down during use, this could cause blood to stop circulating throughout the body.

![image[14]](https://safepatientadvocate.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/image14.png)

– Daniel Keum

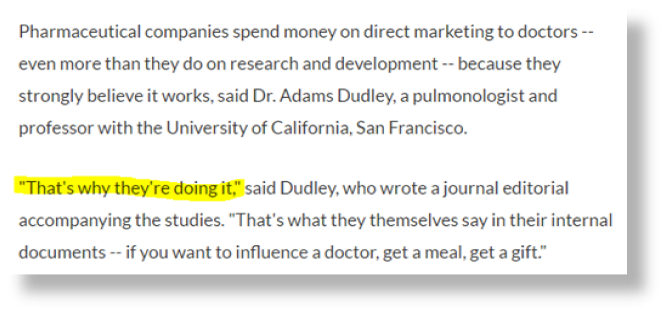

Another great article on the topic of doctors getting money from drug and device companies. Here’s the part that rings most true to me (highlights mine):

The FDA recently issued a Class I recall, the highest level of a recall, on the Newport HT70 and HT70 Plus ventilators. These devices provide breathing support for those who can’t breathe on their own. The company which owns the ventilators, Medtronic, is recalling the ventilators after they discovered a software glitch could shut down the device without warning. For those who require continual ventilator support, this is bad news. The ventilators could turn off without the user knowing, leading to severe health consequences afterwards. A software update from Medtronic to fix the issue is expected soon. In the meantime, users and caregivers of the recalled ventilators should be vigilant when using these devices and, if possible, have a way to monitor the device’s activity when away from the patient. If you are affected by this recall, you can call Medtronic’s Technical Support Department at 800-255-6774.

– Daniel Keum

One of the great myths of medicine is that our physicians are uniquely resistant to attempts by drug and device sales reps to influence the doctors’ judgments on what treatments should be ordered. Doctors are, we are told, independent, objective, and looking out only for us. They see through the sales pitches and focus on the science, for our benefit.

A great story co-published by Pro-Publica and NPR Shots on a new study takes that myth apart. The study in question concerns the effects that drug reps have on the prescribing behavior. In short, the more access the reps have to the doctors at a hospital, the more the doctors prescribe those reps’ name-brand drugs as opposed to generic drugs. As NPR puts it: “When teaching hospitals put pharmaceutical sales representatives on a shorter leash, their doctors tended to order fewer promoted brand-name drugs and used more generic versions instead[.]”

This really shouldn’t be a surprise. Doctors are humans, subject to the same cognitive biases, incentives, and influences as the rest of us. The device and drug companies know this, which is why they send their reps out in droves to try to create relationships with the doctors. But even so, many of the doctors don’t believe they have the same weaknesses as the rest of us.

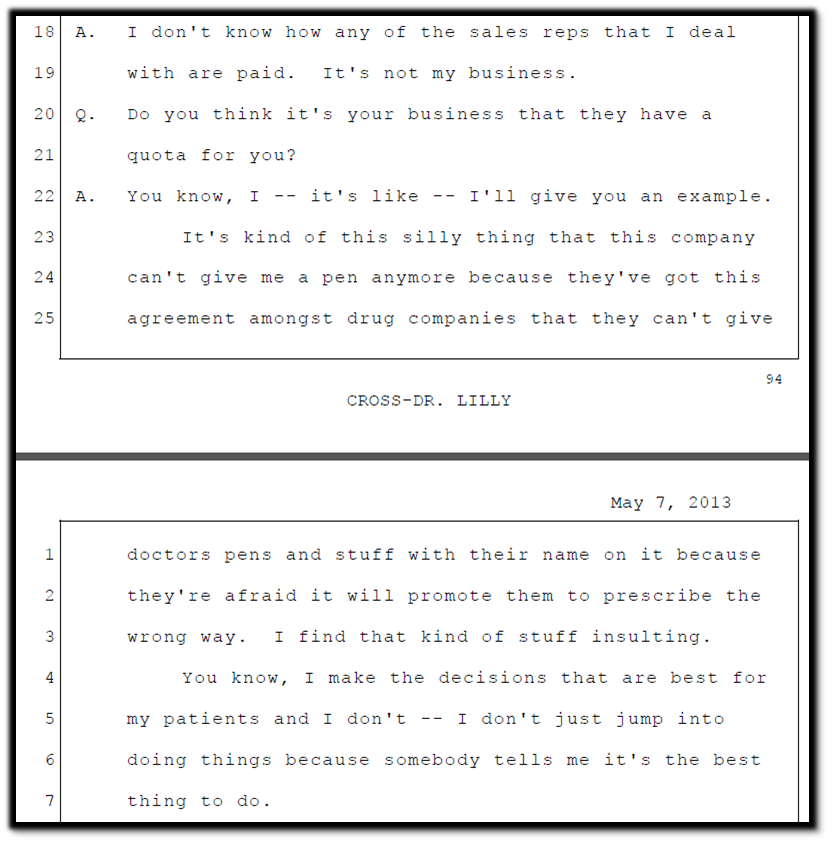

The article particularly reminds me of an exchange from one of our medical device trials against the maker of the “da Vinci” robot, Intuitive Surgical. Part of our case was that our deceased client’s surgery should not have gone forward given the inexperience of the surgeon, but that an Intuitive sales rep had encouraged the surgeon to think he was qualified to handle the surgery. We showed that Intuitive actually had quotas for each of the surgeons at the hospital: i.e., the sales reps were expected to make sure the surgeons did a certain number of “da Vinci” surgeries each quarter, and the reps’ pay was directly dependent on meeting that quota. At the trial, Intuitive hired a doctor to testify that reps could not have such influence over doctors. My partner Rick Friedman cross-examined him, pointing out that Intuitive actually had a quota for that doctor. Here is the exchange:

The doctor believed restrictions on company access were “silly” and “insulting,” because “I make the decisions that are best for my patients.” But if that were true, the JAMA study would have come out a different way. And if that were true, it’s very unlikely that drug and device companies would spent $7.33 Billion on goodies for doctors in 2015 alone. The companies spend the money because it works, and that means patients are not receiving truly independent advice from their doctors.

If you’re curious about what drug and device companies are whispering in your doctor’s ear, it’s a great idea to go on the Open Payments website. I don’t let any doctor do anything to me or my family until I’ve looked them up on that website.

Phenobarbital is a drug used to treat seizures in kids with epilepsy. One supplier of the drug is recalling one lot of the pills it sells. The recall follows a complaint where one consumer found 30 mg pills in a bottle labeled as containing 15 mg pills. This raises an overdose risk, and the danger from any overdose is serious: “cardiogenic shock, renal failure, coma or death.”

Phenobarbital is a drug used to treat seizures in kids with epilepsy. One supplier of the drug is recalling one lot of the pills it sells. The recall follows a complaint where one consumer found 30 mg pills in a bottle labeled as containing 15 mg pills. This raises an overdose risk, and the danger from any overdose is serious: “cardiogenic shock, renal failure, coma or death.”

So get the word out: if you know someone with a kid who suffers from seizures or epilepsy, please pass this story along.

This is a topic I’ve been wanting to write about for a while. Then, the other day, I learned I don’t have to, because my friend Tyler Goldberg-Hoss (an attorney who focuses on medical malpractice cases) already described the issue perfectly. Check it out here.

This is a topic I’ve been wanting to write about for a while. Then, the other day, I learned I don’t have to, because my friend Tyler Goldberg-Hoss (an attorney who focuses on medical malpractice cases) already described the issue perfectly. Check it out here.

The gist? Not unless you ask. That’s not a hard-and-fast rule, and there may be cases where the doctor’s inexperience is so important that the failure to tell you about it is deemed malpractice. But the cases to date in Washington have not come out the right way.

So … ask! If you tell a doctor it matters to you, and they don’t tell you, no judge or jury in the world would let them off.

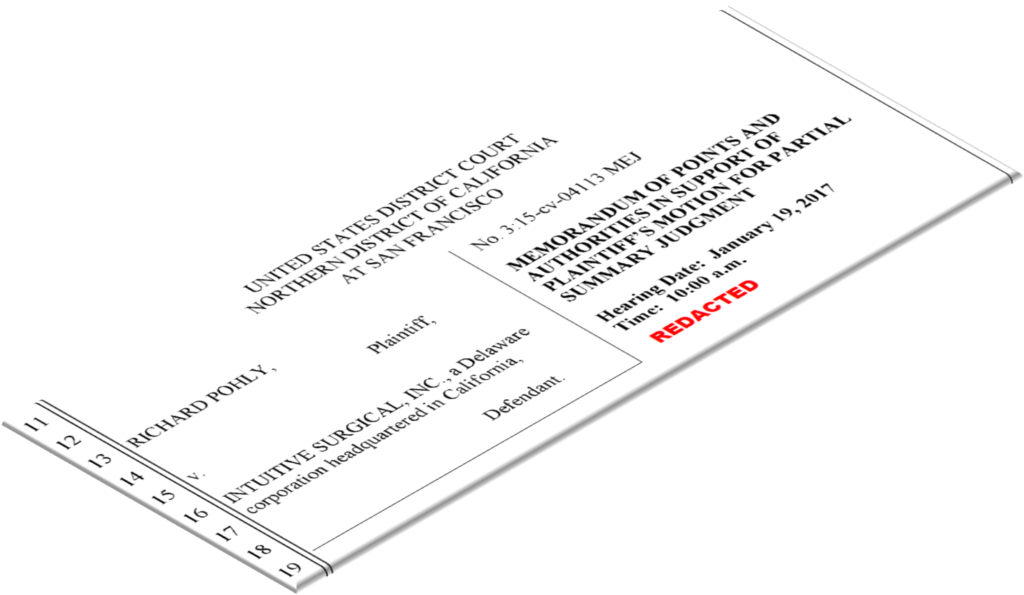

Our firm has brought several cases against the maker of the da Vinci robot: Intuitive Surgical, Inc. The cases I have been most intimately involved in over the past two years are cases involving Intuitive’s recall of its electrified scissors due to “microcracks.” The microcracks matter because they are found in the electrical insulation of the scissors, meaning electricity can come out of the wrong part of the instrument during surgery without the doctor’s knowledge. The result is that people go home from surgery with internal injuries that their doctors don’t know about, those injuries fester, and people get deadly infections with lifelong consequences.

Through the process of discovery, I have had the chance to see all of the internal warning signs that Intuitive ignored from 2009-2013, before it ultimately decided to recall its defective scissors. But until now, due to Intuitive’s legal maneuvers, I haven’t been able to share what I know even with other attorneys representing injured patients, let alone the injured patients themselves or the general public. But that changed recently, when the judge in our case officially declassified most of one court document that sets out the most crucial facts related to what Intuitive knew and when. And so now you can see those documents as well: 2017-03-13 066 Redacted Pl MPSJ Memorandum

If you have questions about these issues, please feel free to email me at safepatientadvocate@friedmanrubin.com

Physio-Control Inc. recently recalled its LIFEPAK 1000 Defibrillator after the company discovered an electrical problem could stop the device from working. The FDA defined this recall as a ‘Class 1’ recall, making it the most serious level of a recall where use of the device can result in “injury or death.” Defibrillators are kept inside hospitals, shopping malls, offices—basically anywhere with lots of people— in the case someone, likely older, suffers from cardiac arrest and needs revival. When used, defibrillators revive someone’s heart by delivering it electric shocks. According to an FDA report, oxidation formation in the wiring of Physio Control’s defibrillator can cause the battery to malfunction and disable the device. If the defibrillator stopped working during an emergency, it would delay or prevent someone from getting electric shocks to their heart. Throughout this delay, blood is not pumping, which means vital organs such as the brain continue to remain oxygen-starved. During cardiac arrest, seconds matter, and the longer someone goes without a beating heart, the greater one’s chances are of organ damage and ultimately death. If you keep this defibrillator in your home or workplace, or depend on one to maintain your heart rhythm, this recall may affect you.

As I wrote earlier, your congress is currently considering a very bad bill, which would drastically remove patients’ ability to be compensated for injuries caused by medical negligence. The last post focused on the proposal to cap non-economic damages. Today’s post focuses on another bad aspect of the law that will lead to valid claims being thrown out of court (or never brought): the statute of limitations.

Section 3 of the law is called “Encouraging Speedy Resolution of Claims.” That sounds good, of course. But what the bill does is bar claims that are not brought within “three years of the procedure.” Most states already have rules of this nature, but they also have three exceptions that keep claims from being thrown out when it would be unfair to do so. The new bill acts to counter those protections as follows:

The bill also recognizes that some states already have more draconian time limitations, and explicitly lets those states keep those limitations.

The first question is: why a federal law? Each state currently has the right to balance these considerations carefully, in the ways their doctors, patients, and voters see fit. A uniform law is not needed.

The second question is: why do we want to do away with meritorious cases in these situations? Why, when the patient did not know there was a claim, do we want to punish the patient? Why, when the patient and the doctor are working together to minimize the damages and avoid a lawsuit, do we want to punish the patient? Why do we want to punish kids who need a lifetime of treatment just because their parents did not realize there was a reason to sue? Why shift that burden to the taxpayers rather than the doctors’ insurance companies, where it belongs?

And will this really work to limit claims? Or will it just make patients bring lawsuits before they have had the chance to fully investigate the claims.

Regardless, you should tell your Congressperson how stupid you think this idea is.

Your congress is currently considering House Bill 1215, which is a really terrible proposal related to medical malpractice cases. The most important things the law would do are these:

My first thoughts whenever I see proposals like this is: why doctors? Why do doctors get special treatment by our laws in addition to exorbitant salaries? Why do for-profit doctors get to say they work at non-profit hospitals? If these laws make so much sense, why don’t we see them for accountants? Architects? Insurance brokers? Estate planners? Financial advisers? Pilots? Truck Drivers? Engineers? Why would we want to remove incentives to act carefully from the people whose negligence can harm us most?

But those initial thoughts aside, each of these individual ideas is terrible. The problem is, none terrible idea in the abstract. You have to look at how each would affect actual people to understand why it’s such a bad idea. To do that, I’m going to look at each of these issues one at a time over the next few weeks. Today we’ll start with the first terrible idea: damages caps on “noneconomic damages”.

Noneconomic damages include things like lost enjoyment of life from an injury: for a man who loved to fly fish but can no longer leave his home, there is compensation. They also include physical pain: for a woman who deals with constant pain during urination because of damage to her urinary tract, there is compensation. Discomfort is addressed by noneconomic damages: for those who can no longer sleep for more than an hour at a time because they cannot get comfortable, there is compensation. And there is compensation for damaged relationships: when a husband and wife can no longer have sex because one is disabled, noneconomic damages address that. When a spouse is no longer there for comfort or companionship, there is compensation.

Noneconomic damages are the realest form of damages, because they concern the things people actually experience. They are the opposite of “economic” damages — things like lost wages and incurred treatment costs — which are simply counted up with invoices and lost pay checks.

The most important thing to remember about noneconomic damages are that they are what keeps us all equally valuable in the eyes of the law. When only economic damages are considered, a blue collar worker’s life is simply not worth as much as a wealthy person’s life. A blue collar worker will not have the same wage loss as a wealthy person. A blue collar worker won’t be able to afford the same high quality follow-up treatments as a wealthy person. So their economic damages will never be as high.

But we all suffer in the same ways. We all experience pain. We all find joys in our lives, and we know the importance of those joys when they are taken away from us. We know how it would feel if our husband or wife were suddenly taken away from us for no good reason. Through non-economic damages we can tell our doctors (and bus drivers, and airplane pilots, and manufacturers) that each life is valuable. So they need to be careful even when no wealthy person’s life is at stake.

The proposed law would remove that incentive.

Imagine a stay-at-home mother of three with an easily diagnosable, highly treatable form of cancer. Imagine the cancer is missed because a for-profit hospital constantly overworked its doctors. Instead of an easy surgery to remove the cancer, she spends the next ten years getting slowly worse. Though she used to exercise frequently, she can’t anymore. She rarely sleeps through the night, which puts pressure on her relationships with her family. She can’t do what she used to do at the home. Her children become her caretakers, which humiliates her and makes her feel worthless. The pain slowly grows until it is constant. She realizes her body won’t sustain her for long. She looks for a lawyer to take her case. She wants to stop this from happening to others. She wants to provide for her family. She wants compensation for what she, and her husband, and her children, have lost.

With the new law in effect, the lawyer now has to look at a case like this differently. The cancer causation expert will run at least $50,000. Another expert will be needed to show the hospital screwed up with its policies. Another $50,000. A third expert to show the cancer should have been caught. Another $50,000. Court reporters, deposition trips, paying to depose the hospital’s experts will all add to the total. The lawyer estimates the cost will be at least $300,000 if the case goes to trial. That doesn’t factor in his normal overhead: leased office space, legal research, staff. The woman’s total medical bills are $500,000 to date, with little more to come. But the insurance company had a deal with the hospital so it only paid 250,000, even though the woman was billed all $500,000. She has no provable lost wages, so that means her “economic” damages are just $250,000.

In other words, she’s got a case worth $500,000 total: $250,000 economic and $250,000 noneconomic. Let’s say the lawyer takes the case on a 40% fee. Even assuming it’s a guaranteed win, it’ll take an incredible amount of his time and effort. And his best case scenario is the $500,000 win, which will let him repay the $300,000 in costs advanced and take the $200,000 as the 40% fee. But the woman and her family will not see a dime in that situation. And regardless, the lawyer knows he could make more on other non-medical cases, with much less risk. So the case does not go forward.

So let’s say the lawyer cuts his fee and takes only 20% ($100,000). That would mean sinking $300,000 into a case that he can only hope to make $100,000 in profit on. That won’t keep the lights on. Even if he wins half of the cases like this, it’s a losing proposition. And the $100,000 the woman actually takes home is nowhere near what would be just compensation for the pain, suffering, discomfort, and fear. It’s nowhere near just compensation for her children losing a mom, her husband losing a wife.

In other words, capping the noneconomic damages means good cases won’t be brought. And that means bad behaviors won’t get caught.

So tell your congress person how stupid you think this idea is.

There is a fantastic story from our local public radio station (KNKX.org) about a confounding trend in the rates of colon cancer for young people vs. those over 50. As the story explains: “Cancer incidence is creeping up by 1 or 2 cases per 100,000 people under 50. By way of comparison, the disease rate among older Americans has plummeted by more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.”

There is a fantastic story from our local public radio station (KNKX.org) about a confounding trend in the rates of colon cancer for young people vs. those over 50. As the story explains: “Cancer incidence is creeping up by 1 or 2 cases per 100,000 people under 50. By way of comparison, the disease rate among older Americans has plummeted by more than 100 cases per 100,000 people.”

According to the story, which analyzes a very recent study out of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, the epidemiologists looking at the issue don’t have a satisfactory answer for why the rate is dropping in the over 50 but increasing in the under 50.

The real fear is that the failure to see the rate decrease in those currently under 50 may mean we see significantly increased rates of cancer in that age group once they reach the age of 50. As the story puts it: “the under-50s will eventually grow older. What will happen to their risk then?”

The recommendation is the thing none of us want to do: get screened via colonoscopy once we reach 50 (the recommended age).

Zimmer Biomet is recalling its “Comprehensive Reverse Shoulder” hardware, which is used in shoulder replacements. According to the FDA, the shoulder pieces are “cracking” at an abnormally high rate. The hardware looks like this and applies to units made between August 25, 2008 to September 27, 2011. This means many of these units are currently helping to move human arms, and that many of those people are now looking at an extra surgery. The units look like this:

One of my pet peeves, since I’ve started tracking recalls, is that manufacturing firms — even though they act as though they are trying to limit harm — make no mention of the recall on the front of their web pages. For instance, Zimmer’s webpage has a section called “The latest news @ZimmerBiomet.” But that section does not mention this news, even the FDA has determined that continued use of this shoulder equipment “may cause serious injuries or death.” See below. (No mention on Zimmer’s twitter feed either.)

Imagine your lawyer failed to get you a necessary expert, and your case got thrown out of court. You’re horribly injured, but now you have no way to recover. This same lawyer had told you your case had a multimillion dollar settlement value. That lawyer is quickly fired by his law firm — but none of that matters anymore, because you’re out of luck.

Imagine your lawyer failed to get you a necessary expert, and your case got thrown out of court. You’re horribly injured, but now you have no way to recover. This same lawyer had told you your case had a multimillion dollar settlement value. That lawyer is quickly fired by his law firm — but none of that matters anymore, because you’re out of luck.

In talking to other lawyers, you realize your lawyer’s error was inexcusable, and you sue him for legal malpractice. But the law firm denies responsibility. It says your lawyer acted reasonably in not getting the expert. And it says your case was terrible anyway. So your new lawyer asks for discovery — all the documents related to the firing and the internal investigation by the law firm that led to the firing. You know there will be evidence in those files contradicting their new defenses. Why else would they have disciplined him?

In a legal malpractice case — you get that information no problem, and you win your case. Same with accounting malpractice. Malpractice by an engineer. Or an architect. A financial planner.

But you’ll never see it in a medical malpractice case in Washington, because of the “QI” (quality improvement) privilege. You can read the statute yourself, but the important part is this: you don’t even get to find out what’s in the hospital’s internal investigation files.

Here’s how it works. Hospitals are required to “maintain a coordinated quality improvement program” for the “prevention of medical malpractice.” To do so, they have to set up “quality improvement committees.” The committee must collect “information concerning the hospital’s experience with negative health care outcomes and incidents injurious to patients[.]” But the information and documents created during the investigation aren’t even discoverable in civil litigation. As the law says: “Information and documents…collected and maintained by, a quality improvement committee are not subject to … discovery or introduction into evidence in any civil action[.]” So if the doctor admits to a screw up during the investigation? You don’t get to know. If the doctor admits to believing you would have done well, absent the screw up? You don’t get to know. If the nursing staff tells the committee they think the doctor screwed up? You don’t get to know.

In other words, the system they’ve set up for “prevention of medical malpractice” is also designed to prevent you from learning what caused your injury in a way that lets you bring a malpractice claim. But there’s no such system in place for other professionals who have to hold themselves to a professional standard of care.

So why the special treatment for doctors? Isn’t it desirable to “improve quality” that prevents other forms of malpractice?

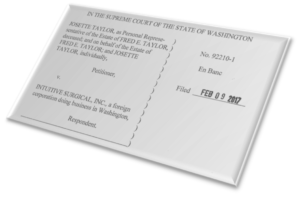

In 2013, our firm teamed up with Otorowski Johnston to hold Intuitive Surgical accountable for the death of Fred Taylor. Our lawsuit chronicled abuses by Intuitive Surgical, the maker of the “da Vinci” surgical robot. Intuitive sold its robot to Harrison Medical Center in Kitsap County, Washington, just like it does to rural hospitals around the country. But Intuitive did not explain to Harrison that the learning curve for using the robot is extremely steep, requiring at least 20 surgeries for “basic competence.” Instead, Intuitive pushed Harrison to allow its surgeons to operate without supervision after only two supervised surgeries. Harrison did so, and our client was his surgeon’s first unsupervised surgery. He died as a result. The original trial was covered by the NY Times.

In 2013, our firm teamed up with Otorowski Johnston to hold Intuitive Surgical accountable for the death of Fred Taylor. Our lawsuit chronicled abuses by Intuitive Surgical, the maker of the “da Vinci” surgical robot. Intuitive sold its robot to Harrison Medical Center in Kitsap County, Washington, just like it does to rural hospitals around the country. But Intuitive did not explain to Harrison that the learning curve for using the robot is extremely steep, requiring at least 20 surgeries for “basic competence.” Instead, Intuitive pushed Harrison to allow its surgeons to operate without supervision after only two supervised surgeries. Harrison did so, and our client was his surgeon’s first unsupervised surgery. He died as a result. The original trial was covered by the NY Times.